10 Things You Must See in the Louvre

The big question the Louvre Museum inspires in most tourists is: When to go and how to avoid the lines? Why not try an afternoon visit on Wednesday or Friday (when the Louvre’s open till 9:45 PM) for a short, focused visit? Leave for a meal (their cafés are overpriced and of poor quality) and return with recharged batteries for a night stroll to another concentrated area. Tip: Your ticket allows you to enter the express lane.

If you stretched out all three wings into a straight line, the Louvre would run a whopping eight miles (14 kilometers). But 80% of visitors just come to take a photo of the Mona Lisa and then leave. There is so much more to see! Dating to 1190, the former palace is ginormous, but glorious — embrace its size, don’t let it intimidate you. And if you want to have an interactive visit dusting off the grandfather of museums, sign up for a themed Treasure Hunt at the Louvre.

Below, our pick for 10 works of art that you must see on a trip to the Louvre.

Below, our pick for 10 works of art that you must see on a trip to the Louvre.

Closed Tuesdays, open till 9:45 pm Wed & Fridays, all other days 9-6 pm; admission 15€

Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa (1503-1506) Seeing La Joconde is a thoroughly unpleasant experience because of the crowds. It’s arguably the most famous painting in the world, due in large part to the hullabaloo that went on in 1911 when she was stolen. Missing for two years, both French poet Apollinaire and Picasso were suspects, before Peruggia (the Italian thief and former Louvre guard) was caught. When hired by François I in 1516, Leonardo brought his treasured painting with him to Château d’Amboise (where he died three years later).

Winged Victory of Samothrace (190 BC, Ancient Greece) The Winged Goddess of Nike presides over the Louvre’s Daru stairs much as she’s perched on the prow of a ship (the grey marble implies the ship’s from Rhodes). Her Hellenistic form merits her place as one of the Louvre’s top three most important pieces. No imagination is necessary to see the wind blowing her cling-wrap thin material or to feel the power of her forward motion and sure-footedness. Meant to be viewed from one angle, note how the sculpture’s roughly hewn on the left. During WWII she was evacuated with the Mona Lisa, Michelangelo’s Slaves & Venus de Milo to Château de Valençay.

Michelangelo’s Dying Slave (1513-1516) Michelangelo’s Dying Slave was meant for Pope Julius II’s tomb, initially commissioned in 1505 and completed on a much-reduced scale in 1545. The writhing, twisting Slave is clearly in agony, standing here in Contrapposto (the figure standing on one leg which holds his weight, the other leg remains lax. This stance prompts the hips and shoulders to rest at opposite angles). This classical pose inevitably gives a curve to the entire torso as seen here. Can you stand in Contrapposto?

Venus de Milo (100 BC, Cyclades, Greece) Aren’t all beauties mysteries? This lady who we all know as the Venus de Milo could have well been an Amphitrite, who the island of Melos (now Milos) worshipped. Art Historians believe she’s a 100 BC replica, however she does have typical 5th Century BC details such as the harmony of her face, her aloofness and impassivity. But many details place her in the Hellenistic period (3rd–1st C BC), such as her spiral composition (You still standing in Contrapposto as you read this?), the fact that she’s 3D, her small breasts and elongated body and most importantly the thin veneer of material draped from her hips.

Lamassus (713 BC), Mesopotamia These protective genies have five legs which from the side appear only as four walking, from the front they’re still and standing “at attention” where pairs of these “Lamassus” guarded each gate to Sargon II’s Mesopotamian capital (at present-day Khorsabad). The city had 24-meter thick walls (the height of a redwood tree!). In the 19th C when the French council was sending these Lamassus back to the Louvre two heart-breaking shipping “incidents” caused much of the excavations to go missing: one through a boat sinking, another lost to pirates… a case for the next Indiana Jones…

Eugène Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People, 1830 Here Lady Liberté (Marianne) champions the Tri-colored French flag (the red, white and blue symbolize Liberty, Equalityand& Fraternity). In fact this painting embodies France to such an extent that it was the face of the 100 Franc (before the € went into circulation in 2002 the currency of France was called the “Franc”.) Marianne is the national figure representing triumph of the French Republic over the monarchy, and as such she appears everywhere from small stamps and euro coins to an oversized statue presiding over Place de la Republique.

Great Sphinx of Tanis (Old Kingdom, 2600 BC, Old Kingdom) The Egyptian appellation for a sphinx was Shesep-Ankh, or “Living Image”, a symbolic representation of the close relationship between sun god (lion’s body) and king (human head). This one was inscribed with the names of the pharaohs Ammenemes II, Merneptah & Shoshenq. Excavated in 1825 among the ruins of the Temple of Amun at Tanis, it’s one of the largest sphinxes outside of Egypt.

Botticelli’s Venus with Three Graces (1483-1486) Fresco painting is a method of painting water-based pigments on freshly applied plaster so that the colors dry within the wall (when the plaster dries), thus becoming permanent. Botticelli painted this fresco on the walls of the Tuscan Villa Lemmi (along with the other pieces in this room – don’t miss Luini’s Adoration of the Magis nearby). Avoid getting trampled by the masses who are coming from Nike of Samothrace and nestle yourself in the corner to really inspect this treasure.

Law Code of Hammurabi

Law Code of Hammurabi (1792–1750 BC, Mesopotamia) Hammurabi’s Law Code is the longest surviving text from Old Babylon and is often considered the first written economic formula. Many laws are still in use, such as interest rates, fines for monetary wrongdoing, inheritance laws concerning how private property is taxed or divided. It’s also one of the earliest examples of the idea of presumption of innocence, requesting that both the accused and accuser provide evidence to make their cases. It’s most famous for its scaled punishments, adjusting an “eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth” as graded depending on social status (of slave versus free man).

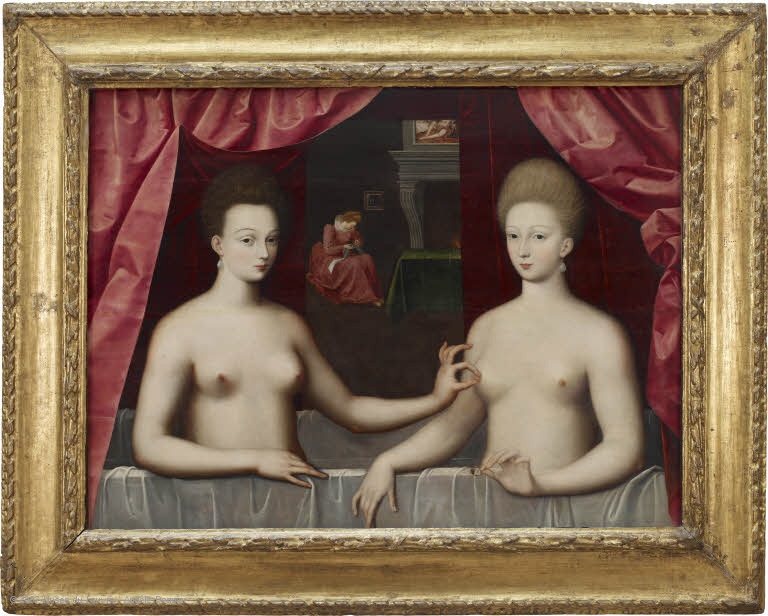

Gabrielle d’Estrées and Her Sister, The Duchess of Villars (1594) An anonymous painting from the School of Fontainebleau, these famous ladies are Gabrielle d’Éstrées (a favorite lover of Henri IV) and her sister, the Duchess of Villars. The fact that her sister is pinching Gabrielle’s nipple has often been taken as symbolizing the latter’s pregnancy with the illegitimate child of Henri IV (Cesar de Vendome). This interpretation is confirmed by the background scene of the young woman sewing – perhaps preparing a layette for the coming child. There are both Italian and Flemish influences, such as the intimacy of the background.