The Magna Carta is seen as one of the most influential legal documents in British history. Indeed Lord Denning (1899 -1999) a distinguished British Judge and second only to the Lord Chief Justice as Master of the Rolls, called the document “the greatest constitutional document of all time – the foundation of the freedom of the individual against the arbitrary authority of the despot”. However, its original conception was not nearly as successful.

The Magna Carta, also know as Magna Carta Libertatum (the Great Charter of Freedoms), was so called because the original version was drafted in Latin. It was introduced by some of the most notable barons of the thirteenth century in an act of rebellion against their King, King John I (24 December 1199 – 19 October 1216).

Increased taxes, the Kings’ excommunication by Pope Innocent III in 1209 and his unsuccessful and costly attempts to regain his empire in Northern France had made John hugely unpopular with his subjects. Whilst John was able to repair his relationship with the Pope in 1213, his failed attempt to defeat Phillip II of France in 1214 and his unpopular fiscal strategies led to a baron’s rebellion in 1215.

Whilst an uprising of this type was not unusual, unlike previous rebellions the barons did not have a clear successor in mind to claim the throne. Following the mysterious disappearance of Prince Arthur, Duke of Brittany, John’s nephew and son of his late brother Geoffrey (widely believed to have been murdered by John in an attempt to keep the throne), the only alternative was Prince Louis of France. However, Louis’ nationality (France and England had been warring for thirty years at this point) and his weak link to the throne as husband to John’s niece made him less than ideal.

As a result, the baron’s focused their attack on John’s oppressive rule, arguing that he was not adhering to the Charter of Liberties. This charter was a written proclamation issued by John’s ancestor Henry I when he took the throne in 1100, which sought to bind the King to certain laws regarding the treatment of church officials and nobles and was in many ways a precursor to the Magna Carta.

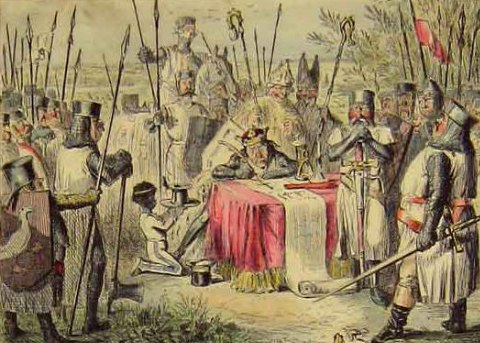

Negotiations took place throughout the first six months of 1215 but it was not until the baron’s entered the King’s London Court by force on 10 June, supported by Prince Louis and the Scottish King Alexander II, that the King was persuaded to affix his great seal to the ‘Articles of the Barons’, which outlined their grievances and stated their rights and privileges.

This significant moment, the first time a ruling King had been forcibly persuaded to renounce a great deal of his authority, took place at Runnymede, a meadow on the banks of the River Thames near Windsor on 15 June. For their part, the barons renewed their oaths of allegiance to the King on 19 June 1215. The formal document which was drafted by the Royal Chancery as a record of this agreement on 15 July was to become known retrospectively as the first version of the Magna Carta.

Whilst both the King and the baron’s had agreed to the Magna Carta as a means of reconciliation, there was still huge distrust on both sides. The baron’s had really wanted to overthrow John and see a new monarch take the throne. For his part John reneged on the most crucial section of the document, now known as Clause 61, as soon as the baron’s left London.

The clause stated that an established committee of barons had the ability to overthrow the King should he defy the charter at any time. John recognised the threat this posed and had the Pope’s full support in his rejection of the clause, because the Pope believed it called into question the authority of not only the King but the Church as well.

Increased taxes, the Kings’ excommunication by Pope Innocent III in 1209 and his unsuccessful and costly attempts to regain his empire in Northern France had made John hugely unpopular with his subjects. Whilst John was able to repair his relationship with the Pope in 1213, his failed attempt to defeat Phillip II of France in 1214 and his unpopular fiscal strategies led to a baron’s rebellion in 1215.

Whilst an uprising of this type was not unusual, unlike previous rebellions the barons did not have a clear successor in mind to claim the throne. Following the mysterious disappearance of Prince Arthur, Duke of Brittany, John’s nephew and son of his late brother Geoffrey (widely believed to have been murdered by John in an attempt to keep the throne), the only alternative was Prince Louis of France. However, Louis’ nationality (France and England had been warring for thirty years at this point) and his weak link to the throne as husband to John’s niece made him less than ideal.

As a result, the baron’s focused their attack on John’s oppressive rule, arguing that he was not adhering to the Charter of Liberties. This charter was a written proclamation issued by John’s ancestor Henry I when he took the throne in 1100, which sought to bind the King to certain laws regarding the treatment of church officials and nobles and was in many ways a precursor to the Magna Carta.

Negotiations took place throughout the first six months of 1215 but it was not until the baron’s entered the King’s London Court by force on 10 June, supported by Prince Louis and the Scottish King Alexander II, that the King was persuaded to affix his great seal to the ‘Articles of the Barons’, which outlined their grievances and stated their rights and privileges.

This significant moment, the first time a ruling King had been forcibly persuaded to renounce a great deal of his authority, took place at Runnymede, a meadow on the banks of the River Thames near Windsor on 15 June. For their part, the barons renewed their oaths of allegiance to the King on 19 June 1215. The formal document which was drafted by the Royal Chancery as a record of this agreement on 15 July was to become known retrospectively as the first version of the Magna Carta.

Whilst both the King and the baron’s had agreed to the Magna Carta as a means of reconciliation, there was still huge distrust on both sides. The baron’s had really wanted to overthrow John and see a new monarch take the throne. For his part John reneged on the most crucial section of the document, now known as Clause 61, as soon as the baron’s left London.

The clause stated that an established committee of barons had the ability to overthrow the King should he defy the charter at any time. John recognised the threat this posed and had the Pope’s full support in his rejection of the clause, because the Pope believed it called into question the authority of not only the King but the Church as well.

Sensing the failure of the Magna Carta in curbing John’s unreasonable behaviour the baron’s promptly changed tack and reinitiated their rebellion with a view to replacing the monarch with Prince Louis of France, thrusting Britain head long into the civil war known as the First Baron’s War. So as a means of promoting peace the Magna Carta was a failure, legally binding for only three months. It was not until John’s death from dysentery on 19th October 1216 whilst he was mounting a siege on the East of England that the Magna Carta finally made its mark.

Following fractions between Louis and the English barons, the royalist supporters of John’s son and heir, Henry III, were able to clinch a victory over the barons at the Battles of Lincoln and Dover in 1217. However, keen to avoid a repeat of the rebellion, the failed Magna Carta agreement was reinstated by William Marshal, the young Henry’s protector, as the Charter of Liberties – a concession to the barons. This version of the charter was edited to include 42 rather than 61 clauses, with clause 61 being notably absent.

On reaching adulthood in 1227, Henry III reissued a shorter version of the Magna Carta, which was the first to become part of English Law. Henry decreed that all future charters must be issued under the King’s seal and between the 13th and 15th centuries the Magna Carta is said to have been reconfirmed between 32 and 45 times, having last been confirmed by Henry VI in 1423.

It was during the Tudor period however, that the Magna Carta lost its place as a central part of English politics. This was partly because of the newly established Parliament but also because people began to recognise that the Charter as it stood arose from Henry III’s less dramatic reign and Edward I’s subsequent amendments (Edward’s 1297 version is the version of the Magna Carta recognised by English Law today) and was no more extraordinary than any other statute in its liberties and limitations.

It was not until the English Civil War that the Magna Carter shook off its less than successful origins and began to represent a symbol of liberty for those aspiring to a new life, becoming a major influence on the Constitution of the United States of America and the Bill of Rights, and much later the former British dominions of Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the former Union of South Africa and Southern Rhodesia(now Zimbabwe). However, by 1969 all but three of the clauses in the Magna Carta had been removed from the law of England and Wales.

Clauses still in force today

The clauses of the 1297 Magna Carta which are still on statute are

Clause 1, the freedom of the English Church.

Clause 9 (clause 13 in the 1215 charter), the “ancient liberties” of the City of London.

Clause 39 (clause 39 in the 1215 charter), a right to due process:

“No free man shall be arrested, or imprisoned, or deprived of his property, or outlawed, or exiled, or in any way destroyed, nor shall we go against him or send against him, unless by legal judgement of his peers, or by the law of the land.”

Following fractions between Louis and the English barons, the royalist supporters of John’s son and heir, Henry III, were able to clinch a victory over the barons at the Battles of Lincoln and Dover in 1217. However, keen to avoid a repeat of the rebellion, the failed Magna Carta agreement was reinstated by William Marshal, the young Henry’s protector, as the Charter of Liberties – a concession to the barons. This version of the charter was edited to include 42 rather than 61 clauses, with clause 61 being notably absent.

On reaching adulthood in 1227, Henry III reissued a shorter version of the Magna Carta, which was the first to become part of English Law. Henry decreed that all future charters must be issued under the King’s seal and between the 13th and 15th centuries the Magna Carta is said to have been reconfirmed between 32 and 45 times, having last been confirmed by Henry VI in 1423.

It was during the Tudor period however, that the Magna Carta lost its place as a central part of English politics. This was partly because of the newly established Parliament but also because people began to recognise that the Charter as it stood arose from Henry III’s less dramatic reign and Edward I’s subsequent amendments (Edward’s 1297 version is the version of the Magna Carta recognised by English Law today) and was no more extraordinary than any other statute in its liberties and limitations.

It was not until the English Civil War that the Magna Carter shook off its less than successful origins and began to represent a symbol of liberty for those aspiring to a new life, becoming a major influence on the Constitution of the United States of America and the Bill of Rights, and much later the former British dominions of Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the former Union of South Africa and Southern Rhodesia(now Zimbabwe). However, by 1969 all but three of the clauses in the Magna Carta had been removed from the law of England and Wales.

Clauses still in force today

The clauses of the 1297 Magna Carta which are still on statute are

Clause 1, the freedom of the English Church.

Clause 9 (clause 13 in the 1215 charter), the “ancient liberties” of the City of London.

Clause 39 (clause 39 in the 1215 charter), a right to due process:

“No free man shall be arrested, or imprisoned, or deprived of his property, or outlawed, or exiled, or in any way destroyed, nor shall we go against him or send against him, unless by legal judgement of his peers, or by the law of the land.”

And what of the Magna Carta’s relevance today?

Although the Magna Carta is generally thought of as the document that was forced on King John in 1215, the almost immediate annulment of this version of the charter means it bears little resemblance to English Law today and the name Magna Carta actually refers to a number of amended statutes throughout the ages as opposed to any one document. Indeed the original Runnymede Charter was not actually signed by John or the baron’s (the words Data per manum nostrum which appeared on the charter proclaimed that the King was in agreement with the document and, as per common law at the time, the King’s seal was deemed sufficient authenticity) and so would not be legally binding by today’s standards.

Unlike many nations throughout the world the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Irelandhas no official written constitution, because the political landscape has evolved over time and is continually amended by Parliamentary acts and decisions made by the Courts of Law. Indeed the Magna Carta’s many revisions and subsequent repeals means that in reality it is more of a symbol of freedom of the (not so) common people in the face of a tyrannical monarch, which has been emulated in Constitutions throughout the world, most famously perhaps in the United States.

In perhaps a telling sign of the opposing views of Briton’s today, in the BBC History’s 2006 Poll to find a date for ‘Britain day’ – a proposed day to celebrate British identity – 15 June (the date the King’s seal was affixed to the first version of the Magna Carta) – received the most votes of all historical dates of significance. However, in an ironic contrast a 2008 survey by YouGov, the internet-based market research firm, found that 45% of British people did not actually know what the Magna Carta was…